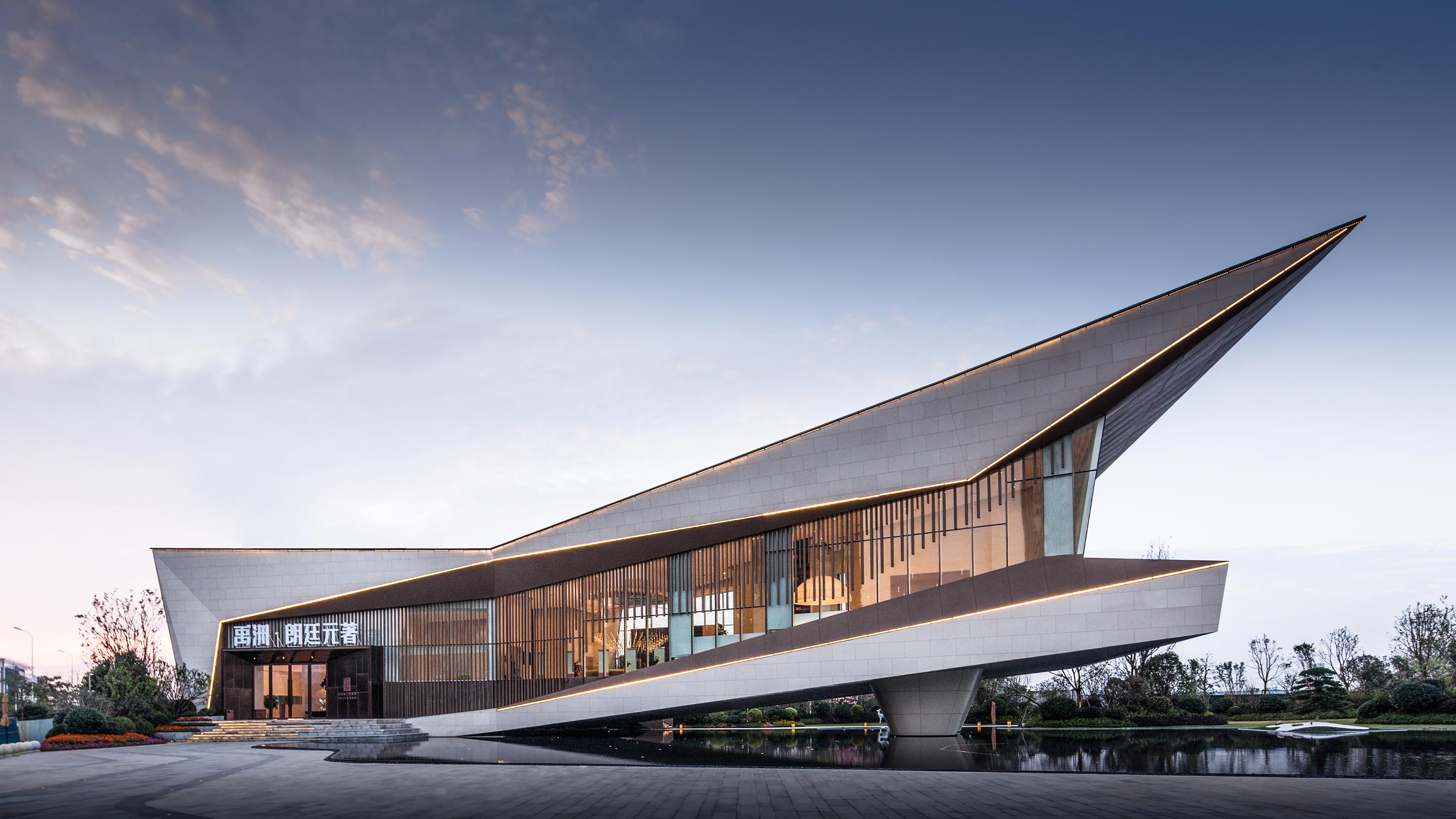

I sat down with Benedict Zucchi, Principal and Head of Architecture at BDP, to talk about his book Big House, Little City. In our conversation, Benedict talks about his early interest in Italian architect Giancarlo De Carlo and other voices in architectural place-making, and how it has guided him in his own work at BDP and the new National Children’s Hospital In Dublin; Ireland’s largest ever public building project, which he is leading.

Karl van Es

Benedict, thank you so much for sitting down with me to discuss your book and experiences in architecture. As a practicing architect, what inspired you to write Big House, Little City?

Benedict Zucchi

The origin goes back to when I first took an interest in the work of Italian architect Giancarlo De Carlo. I came across his work in Urbino in an architectural magazine, and then wrote my university dissertation about him.

As I looked into his work, I learnt about his participation in Team 10 (an avant-garde international group of architects that formed an influential think tank, meeting regularly from the 1950s through to the 1980s). It was Team 10 who started to really popularise the phrase at the heart of my book. It comes from Leon Battista Alberti, the renowned Renaissance architect and polymath. In his famous treatise, ‘De Re Aedificatoria’ (On Building in Ten Books), Alberti posed the question:

“If (as the philosophers maintain) the city is a big house and the house in turn is like a little city, cannot the various parts of the house be considered miniature buildings?”

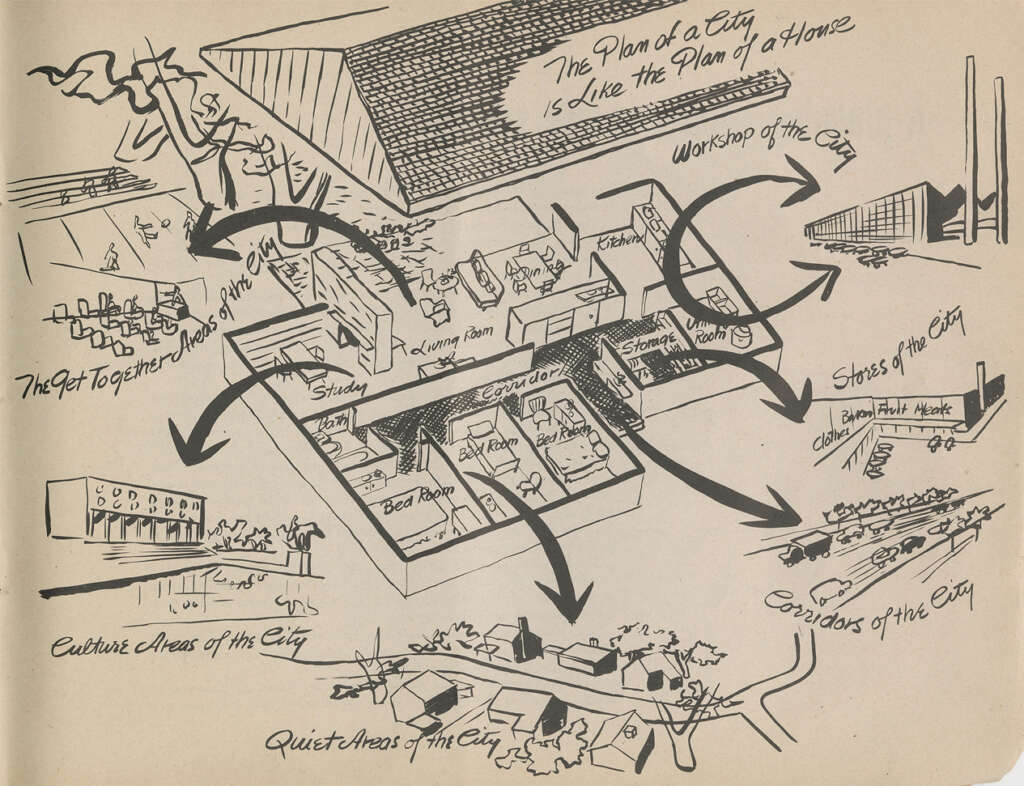

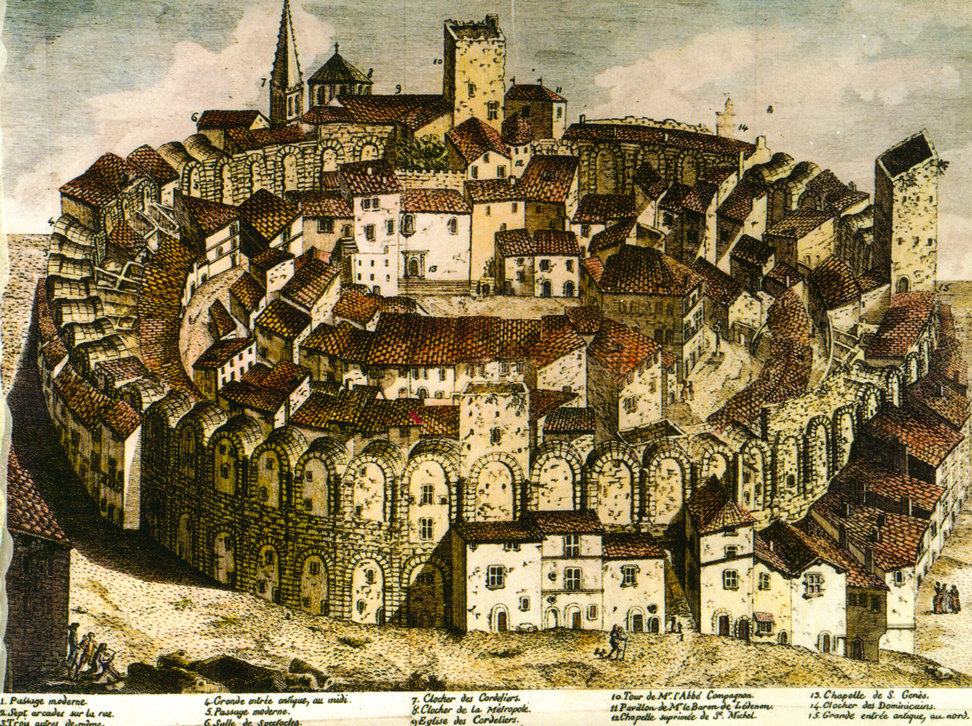

This phrase was of great interest to De Carlo, but it was also an inspiration to Aldo van Eyck from Holland, as well as others in Team 10 like Shadrach Woods. It was also picked up by Louis Kahn, who made a drawing in the 1950s with the caption: ‘the plan of a city is like the plan of a house’. All of them experimented in their own way with the idea of designing buildings as little cities. The most celebrated projects of this type from that immediate postwar era are Van Eyck’s Amsterdam Orphanage and Woods’ Free University of Berlin, which set off a trend for urban inspired designs that came to be dubbed ‘mat buildings’. Giancarlo De Carlo’s Collegio del Colle, a residential college for the University of Urbino, was another early exemplar – a miniature student hill town, an Italian counterpart to Moshe Safdie’s Habitat ’67 modular hill village designed around the same time. You can see the influence of these early experiments on later work by architects like Denys Lasdun, for example his student housing at the University of East Anglia, or more recently BIG’s Mountain housing outside Copenhagen.

Karl van Es

That’s interesting. What do you think it was about Giancarlo De Carlo’s background that inspired him to think about buildings in this way?

Benedict Zucchi

Well, I think it’s to do with being Italian and growing up in the historic context of Italian cities and countryside. Anyone who goes to Italy can’t help but be struck and moved by the historic fabric; not just its urban manifestation in towns but also in the landscape, where natural and man-made layers intertwine inextricably and beautifully. Not all Italian architects after the Second World War were as interested in the historic heritage as he was; he stood out because of his insistence that it was crucially important to conserve and enhance that heritage for what we would now call sustainable reasons. People then didn’t use the word sustainability, but it was a key element of his thinking, which included what today we would call social value. He knew that erasing people’s memory of their past by creating a brave new world of modernist design where everything looks the same was likely to be very dispiriting. It was tantamount to treating people as though they’re some kind of abstraction. He argued, along with many of his Team 10 colleagues, that architectural interventions need to be ‘grounded’ in their physical and social context. People are part of real communities in a specific context with a specific history. De Carlo really cared about the context and understood it both in terms of its physical aspects (the topography, flora, climate) but also in terms of the people who live there, and their vernacular building traditions. De Carlo’s commitment to working within a social context made him a pioneer of user participation, which was the other strand of his approach that really interested me.

So Giancarlo De Carlo, already in the 1950s and 60s, was saying that we must think about the way people use buildings and redefine the role of the architect. The obligation of the architect, he would say, is to talk to people, and to test ideas with them. That’s particularly important for residential projects, but it’s an important ingredient, or should be an important ingredient, in all projects.

Karl van Es

That’s interesting because it seems like design thinking since then has gone in the opposite direction from what De Carlo was saying, towards a Starchitecture and a big idea that doesn’t really have a contextual meaning behind it. Having said that, it seems like today we’re moving away from that and back into looking at site and the social reasons behind building.

Benedict Zucchi

I think the link to Alberti’s house-city phrase is that you can’t talk about architecture meaningfully without talking about environment, which more often than not means urban spaces.

But it’s not just about urban spaces. It’s really about the total environment; the kind of ecosystem that includes buildings, public realm, city spaces, gardens, landscape, the surrounding countryside and region. What I think is fascinating about Alberti’s phrase is that it brings those things back into dialogue with each other. I think Alberti understood that the house is really a proto-city, the seed of a future settlement. All villages start with a community, whose smallest social unit is the family in their home. The extended family, and then a combination of families, make up a tribe or a clan. The houses together form a village. The very word village comes from the Latin word villa. The French word for town, ‘ville’, has the same etymology. So really, the village is a physical extension of a big house. Many of the communities in Europe after the decline of the Roman Empire were built around the remnants of Roman villas. This illustrates the kernel of Alberti’s thesis that the future form and evolution of a city has its seeds in its smallest building blocks, houses.

The thrust of my book is that we must recover the symbiosis between small and big, house and city, architecture and urbanism, because for too many years now we have operated in silos. Urban designers do their thing, town planners do theirs, and they’re often dominated by considerations of economics or transport. Architects are often in their own silo designing self-contained object buildings, the offspring of the International Style, which ignore their context. This professional segregation is the product of an education system that is itself segregated, so the silo mentality continues to be perpetuated.

Karl van Es

In your book you mentioned the works of van Eyck and Aalto. Are there any specific projects that you think are strong examples of this theory in practice?

Benedict Zucchi

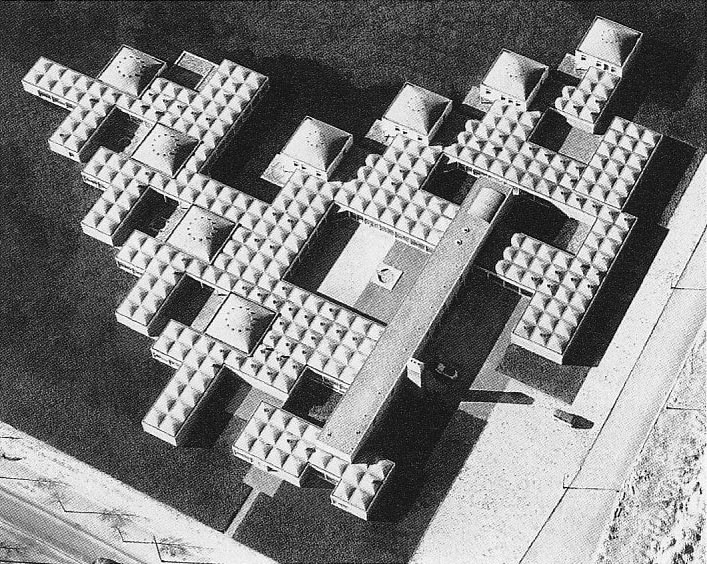

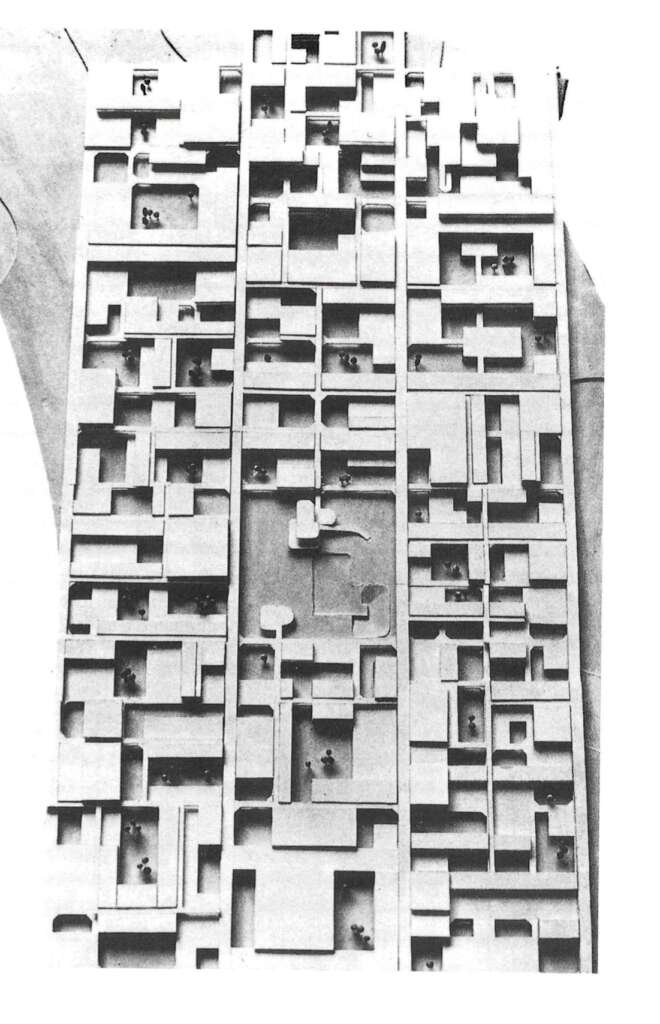

Absolutely, yes, and a few of them became emblematic of the Team 10 mantra. I would say Aldo van Eyck ‘s orphanage in Amsterdam was one of those. It was an institution for children of different ages, who would live and learn there. In plan it looks like an agglomeration of individual houses and school buildings clustered around spaces of circulation. But the circulation spaces are never just about moving through: they are in themselves like a sequence of urban spaces that include informal areas for people to meet and play, what Van Eyck called “in-between spaces”. They are reminiscent of the streets and alleys of a dense medieval city. Team 10 used to delight in talking about the ‘casbah’ and recreating the quality of North African and Arabic settlements, where you got this dense fabric of spaces – a weave of architectural and urban rooms.

So that was one emblematic project; another was the Free University in Berlin, designed by Shadrach Woods and Georges Candilis in the ‘60s. It was a competition win and only partially realised, but it was nevertheless very influential. The architects consciously shunned the usual campus format of separate faculty buildings in favour of a single two-storey weave of teaching and social spaces that they believed would foster greater interaction and be more amenable to adaptation and growth, just like a city. The project was undoubtedly the inspiration for Le Corbusier’s famous unbuilt design for a new hospital in the heart of Venice. Alison Smithson, who was also one of the leading lights of Team 10, coined the term mat building for this typology.

But it was not just Team 10 who brought an urban perspective to architectural design. One of the most brilliant architects to work in this way was Alvar Aalto. From his earliest days, Aalto was fascinated by Italy. He went there on his honeymoon in 1924 and regularly thereafter. Aalto always talked very fondly about Tuscany in particular. It wasn’t so much the grand architecture that he recorded in his sketches and descriptions but the vernacular of small hill towns, perfectly nestled into the landscape; the product of organic growth over many centuries. I think you can see that inspiration very clearly in buildings like his Säynätsalo Town Hall – the approach of clustering buildings around urban rooms. At Säynätsalo the library and town hall are folded around an elevated town square, reached by flights of steps that give one the distinct feeling of moving up through a small hill town.

In his university projects, the urban grain is expressed through covered streets, always beautifully daylit from above. These form the kind of congregation spaces (Van Eyck’s in-between spaces) where people mingle, interact, have a coffee on their way into a lecture theatre or classroom.

I think one of the things that this facilitates, and you can see that very clearly in Aalto, is the ability to tune buildings to their context, because if you start with a preconceived form, a perfect form driven by an ideal grid, you’re going to find it difficult to adapt it to the specifics of its site (topography, mature trees, vistas, climate, historic buildings, routes), as well as considerations of use.

Functionalism in the hands of some architects became a very arid, reductionist exercise, whereas in the hands of somebody as masterful as Alvar Aalto or Louis Kahn, function becomes another strand to his inspiration, one that encompasses not just the ergonomics of use but also the experiential and psychological dimensions as well. His lecture theatres express their use as soon as you see them from outside. They always stand out as ‘buildings within the building’, whose convexity advertises their arena-like function – direct descendants of the iconic Greek theatres carved into the landscape. You can see that same thinking in the work of Jørn Utzon, for example in his Kuwait Parliament, which could be considered a mat building; a grid of streets punctuated by the great assembly halls that are immediately legible from outside in the same way as Aalto’s lecture theatres at Otaniemi University in Helsinki. The Scandinavian tradition of conceiving architecture in an urban way continues in the work of Niels Torp, the veteran Norwegian architect. His innovative office headquarters for SAS and British Airways, or his remarkable Business School in Oslo, are subdivided into separate buildings linked by covered streets and bridges. All primary movement, whether on the ground, upper levels or in lifts, is part of the street life, encouraging informal interaction which draws people together.

Karl van Es

How do you think other contemporary architects that are working in this space are translating this into their own work while recognizing modern challenges, whether they be economic, social or sustainable?

Benedict Zucchi

I think the drive to sustainability is tending to force us to reappraise cities. In the post war era, there were a lot of anti-urbanists, and there was definitely a strand in modernism that was very anti-urban. Symptomatic of this attitude was the deterioration of downtown areas, and the flight to the suburbs.

In the 60s and 70s, New York was declining rapidly, and so was London. For decades, the population kept sliding downwards, and then gradually, over the last 30 years or so, cities have been reviving, as people have rediscovered their virtues. If you live in a city with a reasonable level of density, it’s actually better for the environment and faster to get around. You use less land, less energy; you don’t have to use your car, you can live closer to work. In the Middle Ages, the fact that people worked and lived in close proximity meant that communities were compact and land was used sparingly. People lived over the shop. Perhaps the most famous example that comes to mind is Stradivarius, the great luthier from Cremona in northern Italy. He lived in the same building in which he and his apprentices made violins, selling them in the shop at street level – a model of what we now call mixed-use urbanism. This was the kind of combined living, working and retail which was shunned by orthodox International Style modernists in the immediate pre-and-post war years. They believed in strict subdivision of cities into separate functional zones. Some of the intentions might have been commendable (for example, the aim of keeping industrial pollution away from homes) but the results were disastrous, especially when combined with car-driven transport planning. Thankfully, urban thinking has now come full circle and the consensus is that we need to create denser, more vibrant mixed-use cities with good public transport and as much space as possible for people to walk and cycle. And we’re also reconsidering the layering of our cities so that they’re not just mixed use in plan but also more interesting in their interpenetration of uses in a vertical dimension. The aim, as with BDP’s own Good City initiative, is to promote solutions that are more sustainable by being more context appropriate.

So architects are beginning to explore much more complex building typologies with different uses on different levels, and I think this is where the work of WOHA is interesting, and complimentary to our philosophy at BDP. In projects, like WOHA’s Kampung Admiralty in Singapore (a single mixed-use building) or BDP’s Liverpool One (an entire mixed-use urban neighbourhood) architects are playing with topography, creating multiple ground levels – a kind of vertical urbanism. This strategy mitigates the scale of large buildings, helps to subdivide a building into segments related to different uses, and provides more green space. The integration of landscape, urban design and architecture is crucial. Green space is vital to counteract the urban heat island effect, improve retention of water, augment the amount of vegetation and habitat, and improve people’s views and amenity.

If you look at the National Children’s Hospital in Dublin, designed by BDP, we’ve done exactly that. We have created what is set to become Europe’s largest roof garden halfway up the building, where it forms the base of the ward pavilion housing the majority of children’s bedrooms. All the children in the wards enjoy this extensive raised ground level, which is the foreground to all the bedrooms. You really don’t realise that you’re several storeys in the air when you’re up there. So, in that sense it’s very effective as a way of grounding this part of the hospital, imparting human scale to what is a huge 165,000 square metre building – with a daytime population of several thousand people, who work, learn, meet and reside there, it’s a literal city, not just a metaphorical one.

Karl van Es

Yes, I was going to bring up your Children’s Hospital in Dublin because you’ve talked about villages in Italy and your design processes, and I imagine things like a Nolli map, where you’re seeing a stripped-down version of a city in black and white spaces, influenced your design for the hospital, particularly with spaces like corridors reconceived as streets.

Benedict Zucchi

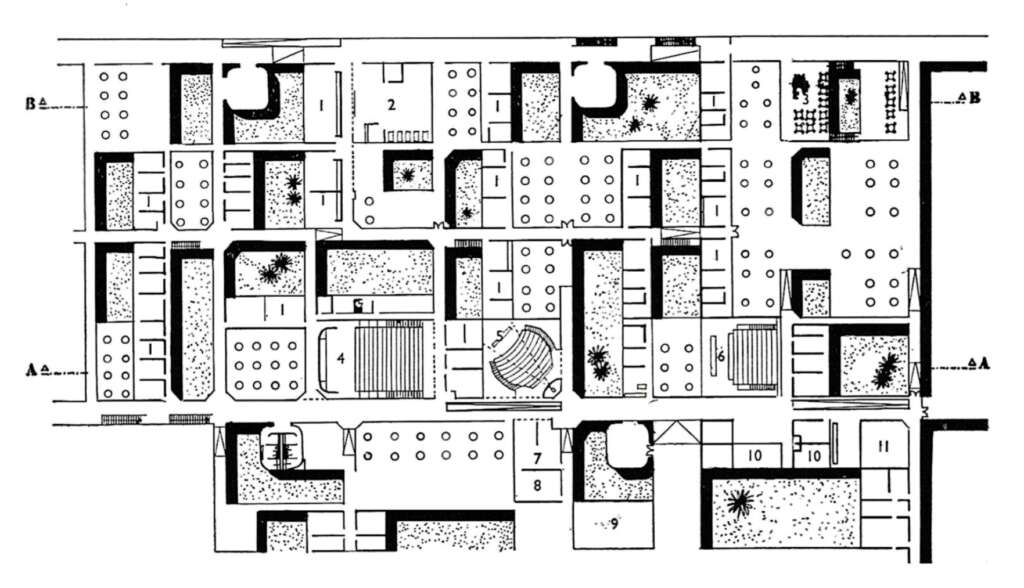

Yes, I think the beauty of the idea is that it really is scalable. In the context of a hospital, you might start with an idea about how the bedrooms are grouped. At NCH we cluster the bedrooms around a shared staff and social space, which acts like a mini town square or maybe a courtyard in a house. We then repeat the cluster, so you get groups of eight bedrooms with this shared amenity space. And then three of these neighbourhoods form a ward, which is given a specific identity and may be associated with a particular group of patients who come to consider it a ‘home away from home’. Then, in the case of Dublin, four wards combine together to form a courtyard and they have a large sheltered garden as a shared amenity. We’ve applied the same logic to the whole building, subdividing it into different neighbourhoods, which are legible as ‘buildings within the building’. These different building typologies are related to the grain of the spaces they house. So, in addition to the oval ward pavilion and Rainbow Garden, we have an acute block which houses the bigger grained spaces like operating theatres, imaging suites, critical care and emergency departments. We also have a series of finger blocks, which echo the scale and orientation of the Victorian terraced houses opposite. These accommodate the outpatient clinics, grouped around shared courtyards and waiting areas.

When we started the project, we consciously thought about it in urban terms, taking our cue from Alberti. And drew plans of each level in the style of Nolli’s map of Rome, so that the internal street pattern was highlighted. We set up what we felt was a strong urban alignment anchored by an atrium street. This forms the north-south spine of the hospital, with public entrances at both ends and its midpoint. Then we thought about the buildings that would fall into place around this urban mould – which parts were best suited to which functions. The beauty of this approach is that it provides a robust scaffold for meaningful user engagement. Each of the clinical neighbourhoods can develop autonomously in dialogue with the users. We had multiple rounds of meetings with hundreds of people, including children, young people and families, over a span of two or three years.

The urban model was very effective because it meant you could give the project a sense of direction (an urban grain), and get people excited about the vision, but without constraining their ability to make a meaningful contribution to the dialogue about the area that they were responsible for. So, just like a house in a city, each part could be extended or modified without jeopardising the overall character of the street or district. Think of each house in that metaphor as somebody’s home. The family can adapt, enlarge, furnish and appropriate their dwelling, so that over time the building, and by extension its neighbourhood, evolve incrementally – people shape their environment but in turn are also shaped by the environment. This process is described very beautifully in Stewart Brand’s book, How Buildings Learn – what happens after they’re built. In an urban context, it’s important to see the individual house or building as part of a street, which provides the unifying idea binding together the urban form. So, in the hospital context, I think the methodology I’ve taken from Alberti has proved a very effective strategy, one which we’ve deployed over many projects now.

Karl van Es

I’m wondering about how this model applies to building adaptation and city building. For instance, when you think of ancient cities like Rome and London that have built been built over ages, Rome seems quite ancient still, with very little notable contemporary architecture whereas in London there is a more visible continuation of history. Drawing a comparison to architecture and your previous Amsterdam Orphanage case study, that is a building which demonstrates your thinking; however, it no longer serves its original purpose.

Benedict Zucchi

Well, I think the beauty of this urban approach to architectural design is that it can accommodate change and growth. It sets things up for the future. A perfectly symmetrical, isolated building, perhaps at the end of a grand vista, may be appropriate for a royal palace or something monumental; a certain type of building, or a certain situation. But it tends to preclude adaptation.

If you think more realistically about an urban context, the kind of buildings we’re designing at BDP, especially hospitals which need to be adaptable, there are two kinds of change that we have to address. There’s change that needs to occur in the course of the design process, which on many of these larger projects is a long period in itself. In the case of Dublin, it will be close to 12 years from design inception to inauguration. Bear in mind that those years were preceded by a further decade of preparing the brief and the clinical business case, gaining political support and putting in place the finance and procurement. So, we’re talking about a 20 -25-year span. Now that might not be typical of most projects, but at the larger end of the spectrum it is probably not unusual, especially for big urban regeneration projects, like Liverpool One or King’s Cross in London. Those are projects that have taken a generation or more to develop up to today. But successful cities have lifespans that are measured in centuries, so our design approach needs to cope not only with change in the course of design and construction or the first years of operation; it also has to address the need for longer term growth and change. To be sustainable, cities must be able to adapt, whilst retaining the best of the past. Sense of place, I think, is really important as a foundation for the future. Viewing architecture through an urban lens is absolutely about sustainable place-making – designs that people identify with and take to heart, so they become cherished parts of their local townscape that they want to preserve and adapt.

Karl van Es

I think that’s a good way to frame it. One of the things I would like to ask as we near the end of the discussion is about your own personal experiences and the things that have shaped you as an architect and thinker. Are there specific cities or buildings that have really inspired you or ones that could even benefit from this approach?

Benedict Zucchi

I often think about Fallingwater, and I don’t know at what point I saw an image of the house, but it was quite early on, probably before I went to architecture school. I was just mesmerised by that famous view. It was a drawing, or it might have been a photo, looking up at the house from below the waterfall. It still has an extraordinary power for me, which kindled my abiding interest in Frank Lloyd Wright. It was not only a supreme expression of modern architecture with its gravity defying cantilevered terraces but also a highly bespoke response to its natural context. Considering Wright’s work as a whole, it seems to me that he had a strong predisposition towards context. I discovered when I first started reading about him that he’d been to Italy, but I didn’t know much about his time there. I then did a seminar course at Harvard with Neil Levine, the art historian and authority on Frank Lloyd Wright. Two of the best books about Wright are by Levine, and I highly recommend them. Neil encouraged me to write a dissertation about the influence of Frank Lloyd Wright on Italian architecture after the Second World War. The Italian architectural historian Bruno Zevi was a great promoter of Frank Lloyd Wright, and made him the centrepiece of his book Towards an Organic Architecture which was a conscious counterblast to Le Corbusier’s Towards a New Architecture. Like Wright, Zevi opposed Le Corbusier’s association of modern architecture with the machine aesthetic and the idolisation of engineering.

Wright had a significant following in Italy and was invited to receive an honorary degree in Venice in the 1950s.

Carlo Scarpa was one of the architects who was most obviously influenced by him. So was De Carlo. What I detected, after reading more about Wright as part of the research for Big House Little City, is that he was sensitive to historic contexts just as much as natural ones. When Wright went to Italy in 1909 and spent a year living in Fiesole above Florence, it was a very significant turning point in his career. As Levine points out and I expand upon in my book, Wright’s designs after 1909 have a different quality from his early Prairie Houses. This is very evident in his own homes, Taliesin North in Wisconsin and Taliesin West in Arizona. I see these as archetypal little cities, not just in their aggregative form and response to context but also in the way that Wright and his Fellowship (his combination of architecture school and office) inhabited them. Wright was absolutely alive to the quality of the landscape and its historic dimensions.

Nothing is really in its purely natural state in Europe because of the many, many sediments of history, so history has almost acquired the character of a natural phenomenon. Perhaps that’s why organic architecture has such a following in Italy.

In the 1960s, Bernard Rudofsky’s famous book and travelling exhibition, Architecture without architects, documented places from all around the world that were beautifully attuned to their locations. These were vernacular buildings and settlements designed without architects, which have an organic quality akin to natural structures. They feel like they’ve sprung from the earth. We know that we’ve made them, but I love the idea that they’ve developed gradually over many, many centuries by multiple hands – a kind of collective work in progress. And if you look at Wright’s projects; the two Taliesins, they are like the nucleus of little cities, the Roman villa that one day will become a village. He was designing little communities, and the way he lived in them was very much in that vein because he and his fellowship were working, learning, cooking, and socialising there.

So, I think in terms of places, there are lots of buildings and cities that inspire me. I love New York, even though some would see it as the ultimate progenitor of anonymous gridded cities around the globe. I think that the grid in New York is more subtle because it is modified by the terrain (the distinctive coastal setting of Manhattan and Long Island) and by history. Broadway traces an old Indian path cutting a diagonal across Manhattan and the original colonial nucleus of the city on the southern tip has its own very rich texture.

I love Rome and discuss aspects of its history in the book. It is a most vivid example of the ebb and flow of a city’s organic growth over many years. At times it looked as though it was in terminal decline and its fabric was being subsumed by nature, its imperial form gradually disintegrating and disappearing into the landscape. But then, over many centuries, its fortunes revived and the ruins became an inspiration for a new cycle of development. I also continue to be fascinated by my home city of London, a metropolis composed out of interconnected villages. I write at length about London in the book because I think it is very much in tune with Alberti’s house-city. Each urban village provides a local focus, with its own high street, public transport nodes, schools and parks. These mitigate London’s overall scale and provide strong local identities to its different districts. They aggregate, like houses in a neighbourhood, to form a network of districts that provide great diversity within the overall unity of London’s metropolitan identity. But this unity is not based on an overriding geometric pattern, like Hausmann’s Paris or the North American gridiron. In London or Rome, the variety comes from the many boundary conditions, the urban equivalent of Van Eyck’s ‘in-between spaces’.

Karl van Es

It’s true, and even when thinking about New York, some of the most successful public spaces and architectural interventions are within the leftover spaces, I’m thinking of the High Line specifically or more recently Little Island by Studio Heatherwick.

Benedict Zucchi

I think it’s an interesting point because one of the things I argue in the book is that we must not allow grids to become the preeminent consideration in the design of buildings and cities. Some architects routinely start a project by saying, well, what’s the grid? And they will spend a lot of time primarily focusing on what the grid should be. This is very common in the world of hospital design, especially in the UK with the latest drive towards standardisation. I’ve always felt that that was absolutely the wrong starting point. One of the most creative and prolific Team 10 architects, Ralph Erskine, would say ‘forget the grid’. That is not the place to start. Think about the activities, think about the space, think about the grain, the transition between private and public and the thresholds between different kinds of spaces. Erskine was another wonderful architect working in an urban vein, whose residential projects remain exemplars of good design, for example his Byker Wall social housing in Newcastle.

Returning to New York for a moment, the interesting thing about Manhattan is that it has strong boundaries, so the grid has a rhythm to it which is not the same in all directions. At Byker, Erskine created his own boundary with a sinuous perimeter block that acted like a fortified wall, sheltering the smaller scale residential terraces from the prevailing wind and the noise from a planned highway. In Manhattan, boundaries are imposed by the existing shape of the peninsula in the first instance but also by man-made interventions like Central Park, or the way the grid interacts with Broadway and so on. This gives Manhattan very distinct neighbourhoods despite the repetitive nature of much of its grid. Christopher Alexander emphasises the importance of boundaries in his book Pattern Language because they are intrinsic to our sense of place.

If you think about a house or a city as a big house, the image implies boundaries. If you’re thinking about a gradual aggregation from house to city, you need some kind of definition at each intermediate scale that provides a local context within the bigger one. Otherwise, you end up with megastructures, whose lack of smaller scale definition feels disorientating, anonymous, bleak. An undifferentiated, boundless grid is a feature of modern cities not only in the horizontal plane but also in the vertical one. Picture skyscrapers; it really doesn’t matter how many floors they have; the grid just carries on forever and there isn’t really a natural limit. The buildings are autonomous, each an isolated object with no capacity to interact with one another because their centre of gravity is so far from the ground. This kind of approach leads to what I call ‘anywhere architecture’, designs produced in a context-free vacuum – a conceptual silo. One of the key aims of Big House Little City is to break down the silos between architectural and urban thinking and encourage us to see them as part of what should be a symbiotic ecosystem, where part and whole, individual and collective, private and public, house and city are in constant dialogue.

Karl van Es

This has been a really enriching conversation. Thank you for taking the time to sit down with me and talk about your book.

Benedict Zucchi

It’s been my pleasure.

Benedict Zucchi, a Principal and Head of Architecture at BDP, studied architecture at the Universities of Cambridge and Harvard. Previous publications include the first English language monograph on Giancarlo De Carlo, the Italian architect and member of Team 10. A close reading of place and use and an abiding interest in user participation have been common threads in Benedict’s projects, which range from mixed-use masterplans, schools and universities to designs for major hospitals. His work has achieved public recognition through a number of prizes, including RIBA Awards for Marlowe Academy and Alder Hey Children’s Hospital and two Prime Minister’s Awards for best public building. He is currently leading the design of the new National Children’s Hospital in Dublin, Ireland’s largest ever public building project.