Karl van Es: Daniel Ibañez is a practicing architect, urbanist and educator. He is Doctor of Design at Harvard University and currently Director and CEO of the Institute for Advanced Architecture of Catalonia’s (www.iaac.net) and principal of Urbanitree design studio (www.urbanitree.com). His professional work revolves around ecological buildings. He is building the tallest social housing mass timber building in Spain, he is co-author of the Mies Van der Rohe pavilion installation Mass is More and is co-author of the book Wood Urbanism: From the Molecular to the Territorial. Also, he is Senior Urban Consultant at the World Bank. Daniel joined me today to talk about the IAAC, his own professional work, and where he sees the IAAC heading in the years to come as it relates to the climate emergency.

Daniel, thank you for joining me and the Avontuura team today.

The IAAC describes itself as a center for research, education, production, and outreach with the mission of envisioning the future habitat of society and building. How do you see the IAAC within this and its role within Barcelona, Catalan culture, and the world abroad?

Daniel Ibañez: Thank you for the invitation. It is my pleasure to be here. Our institution is a very particular one. We are structured as a not-for-profit and were established as an education center that very quickly started to colonize other areas of research and development, which I would now say has three main components.

One that is very centralized is our educational branch. We run more than 10 postgraduate programs with students from all around the world. Roughly 70 to 72 nations have been represented this year, with an average of 300 students. The main characteristic of our programs is that they are all postgraduate, which means that we like to give architects that have a more generalist training a specialization in a particular aspect of study. And I say architects, but in many cases, there are also other disciplines that come to us to get that specific training, given that we are not very disciplinary in nature, meaning we don’t just train architects or designers of buildings.

The second part, which is very relevant, is the research; we discovered that because we are always invested in innovating, we are consistently doing things at the cutting edge. Most of our production, even though sometimes academic, was very connected with that kind of research, and European and nationally funded projects are our platform to keep advancing and keep leading on innovation in the fields that we like to tackle. In this way, we have also discovered in recent years that we could play a very important role in helping companies and other institutions innovate. They don’t often have the structure or capacity to innovate in their specific fields, so for the IAAC [who have been doing it for years], this is something very important to establish more strategic partnerships with industries so we can create these strategic alliances for inserting innovation into their fields.

So those would be the three main things that we do. All our programs are running in English in a very international environment. We have two headquarters, one of which is very close to the city center in a district called 22@. And then we have another campus that is 15 minutes away from Barcelona in a 130 hectares forest that we call the forest campus, where we run programs that are more connected with the natural environment, with materials and production processes that lead to natural solutions, and things like that.

Karl van Es: That’s very interesting. How would you say the two locations fit within Barcelona’s culture or city life itself? Can the public or people who are interested in what you’re doing visit the campuses and see what you’re doing? Or is it more closed off for research and academic purposes?

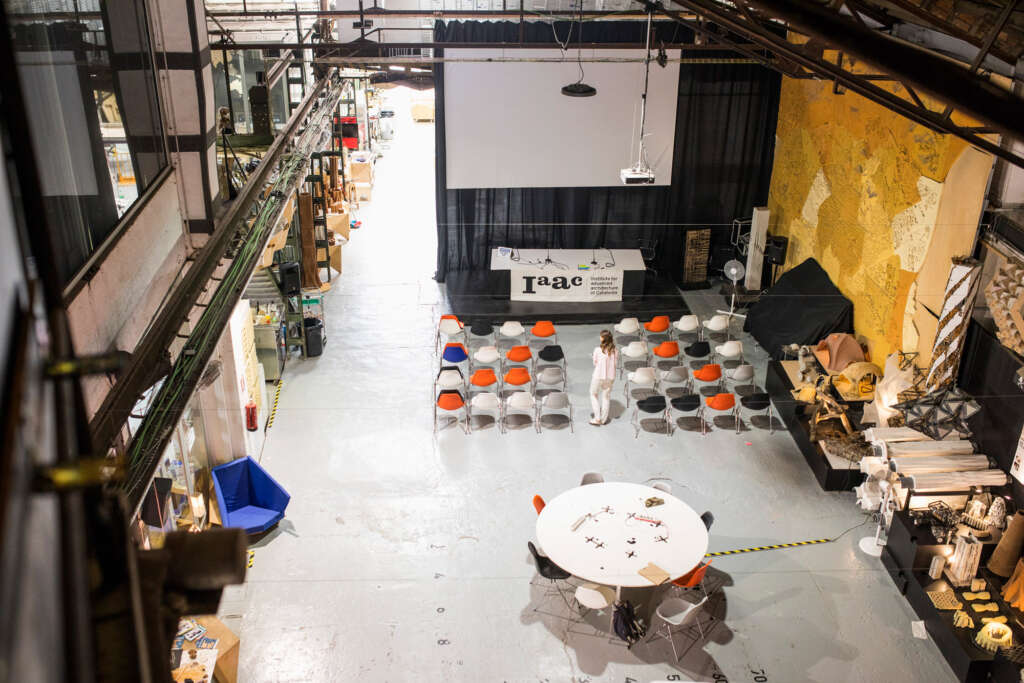

Daniel Ibañez: No, quite the contrary. Our fourth leg, if you will, is about outreach and dissemination. We run a lot of different events that are open to the public. I would say even weekly we have lecture series, for instance, where we invite designers, architects, engineers, biologists, and economists that are relevant to our mission to give lectures, and these are open to the city. On many Thursdays, our headquarters are full of locals and visitors to Barcelona who join us just for that.

Also, in general, we organize a lot of visits because the IAAC has a very deep connection with the culture of detail fabrication. We have a big lab with many machines and fabrication robots, along with many other kinds of tools that people find interesting. We want to train a new generation of holistic designers, architects, and engineers who are also makers and who relate to the material transformation of the world. Not only exploring theoretically what needs to be done but also what makes it practical as well.

Also, our campus in the forest; Valldaura Labs has been getting a lot of attention these days because we have turned what used to be an old Masia, which is a very typical historic construction type in Barcelona, into a research center in the middle of the forest. There, we do sustainable forest management that guides the timber process.

Karl van Es: The Valldaura Labs is actually a great place to go next because one of the projects that really caught my eye, and one that you’ve completed recently is FLORA which I believe stands for the “Forest Lab for Observational Research and Analysis”, and it’s this beautiful observatory and scientific research facility built out of timber. I believe it allows researchers to live and work within the forest canopy. Could you maybe talk about that and what the public reaction to it has been?

Daniel Ibañez: Absolutely. So first, I would say that FLORA is basically the result of a series of generations of master’s programs that we have been running. Valldaura [Labs] right now has this immersive program that is called the “Master in Advanced Ecological Buildings and Biocities,” where we basically receive between 20 and 30 students every year that live with us, and they don’t abandon that campus unless they want to go into the city and enjoy all the things that come with that; but they mostly sleep there, fabricate, learn, study; pretty much everything happens within that immersive environment.

We have this idea of not only learning by making but also learning by leaving, where there is this extra ring of action to the things that we do in the sense that people are not only making things that are relevant for architecture, but also harvesting their own food and materials, doing sustainable forest management, and many other things that come with living.

The program is unique because we think it is very important that students not only get the theory about how to make advanced ecological buildings but also experience the full scope of making a prototype. It’s not only that they design and build, but that they design the “full value chain”. All the final thesis projects for the Master’s program have come from materials in our forests that a student has transformed from being a tree into a finalized prototype.

This is a very important expertise that we want to teach our students; that [education] is no longer only about the technical prescription of elements to build buildings but rather to understand the full value chain, from the sourcing of materials all the way to the final actualization of the building.

For FLORA, we took that framework last year and made a prototype (or laboratory) to observe our tree canopy. This project, I also have to say, emerged out of fantastic research done by Margaret D. Lowman, a biologist and world-renowned expert on tree canopies who helps them predict future impacts of climate change. For instance, just observing the change in insects at the top of trees can provide a lot of information for predicting future impacts. So inspired by this, we decided to do a small prototype, absolutely fabricated by our students and researchers, that could enable a connection with the tree canopies and the four types of tree species that we have at Valldaura, from oak to pine and a few others.

The observatory had to be strategically located to be able to analyze these species. The prototype is inspired by that idea and creates almost a black box condition for a researcher on the inside—a place to keep lab equipment needed to understand the forest from a more digital perspective. And then on the outside, it’s quite the contrary; it’s a very experiential connection with the trees with large bridges that relate to the central core and enable any researcher or visitor to be in connection with the forest at a completely different height. In less than a year of being built, it has received many different visits. People love it because it’s a very special place and piece of infrastructure that provides a special connection with the forest.

Karl van Es: Yes, it sounds incredible, and it seems like the IAAC is very interested in sustainability and the climate crisis in general. What would you say the IAAC’s role in this is in the broader context of addressing things like sustainable buildings and future cities?

Daniel Ibañez: So, at IAAC, we are very driven to train a new generation of designers, architects, engineers, biologists, and multidisciplinary professionals that are invested in tackling this big issue that we have ahead of us (climate change). For instance, we have discovered that for many years, architecture and cities have been built without really taking these issues into consideration. This is horrible for the world, and we’re building at the expense of other territories that were simply not accounted for before. Even when we are trying to obtain sustainable certifications for buildings, we are only ever measuring their operational performance and removing everything that happened before them to make it possible.

So, with many of the innovations that we do, we have this understanding that for us to have a building, first off, you need to source materials from different locations, transform them, and transport them [to a given site]. And we have come to realize that this process is huge [environmentally]. It could even represent 70% of all emissions associated with a cycle, with only 30% being the actual operational emissions that you generate just by using the building. So, with that information, as a designer, I should pay more attention to the value chain that makes buildings than the efficiency that I can squeeze into them.

Once you know this, it makes the use of bio-based materials and research on bio-based materials fundamental, and we research new methods of construction that could be both more efficient and more local. We are really trying to have this idea of a new “bioregionalism”. Instead of this globalized craziness where you can supply materials from every corner of the planet [as if it doesn’t matter], what we’re really trying to do is have a local understanding of the local possibilities, local climates, and local materials to generate the project.

In that regard, it is no coincidence that all the prototypes that we have been making are timber-based because we have a forest that we manage sustainably. For example, we have a fantastic clay soil here that has enabled us to do another line of research that is very important to us, dealing with ceramics and the clay that you can make houses out of.

In this way, I would say we are well positioned within the climate change discussion and are very invested in using renewable materials that come from bio-based sources. We are really trying to keep in mind the full value chain that tells us that we should build more regionally as opposed to this kind of planetary system of moving things from side to side, which is obviously not very sustainable.

Karl van Es: A lot of your professional and academic research has been focused on timber and renewable construction materials. I believe you’re also working on Spain’s tallest social housing building, designed by yourself and Vicente Guallart. I believe it’s called “Terrazas Para la Vida” or “Terraces for Life”. The project looks incredible. It has a good window-to-wall ratio, deep balconies, lots of trees, and organic life on multiple levels. Could you maybe talk about that a little and how that project applies to your thinking and research?

Daniel Ibañez: Yeah, absolutely. Most of my personal research has been around one kind of material flow that is very critical for urbanization, which is timber. I was originally more interested in understanding urban metabolism and the dependencies that occur between cities and the territories around them that supply and support them. But I decided to select timber because it has this dual role where it can not only provide a material to support the act of building cities [that we need to support a growing population], but simultaneously remove carbon and this residue that we have floating in our air, acting kind of like an air filter.

As a result of this research, I published a book called Wood Urbanism – From the Molecular to the Territorial where we are trying to really link what has happened at the forest scale with the details, properties, and propensity of the material itself. I’ve been carrying out many different efforts in this regard, from helping governments in Latin America to setting up public policies that promote this type of construction through my work as a consultant. But for me, as a practicing architect, it is not enough just to consult or teach. We must prove that this is the way to do it.

Terrazas Para la Vida was a competition that basically asked for a design and a budget to do social housing—40 units where they changed the criteria of the competition. Instead of just valuing economic proposals and the quality of architecture, they decided to change the criteria so that 30% of the evaluation would be for the emissions associated with the materials, 30% on the speed of construction, and finally, 30% on prefabrication and industrialization.

The first floor is a concrete structure, along with the foundations. Timber does not work well for foundations, but after that, the eight storeys above the ground are all mass timber, with a lot of innovations baked into the design beyond being the tallest timber building in Spain (which is a landmark in itself).

The building has very large terraces, as you mentioned, as it was designed in the middle of COVID. For us, having access to free air in your domestic space was very important, so we tried to be very generous with that proposition. We also inserted many trees on the balconies and on the rooftop. The ones on the rooftop are also productive in the sense that they are fruit trees that can be harvested and eaten.

On the rooftop, we also have what we called a solar greenhouse. It’s basically a very tall greenhouse to produce food, but it also has solar panels on top that are encapsulated over the glass. It enables light to go through while simultaneously generating energy, so somehow our building enables the production of food and the production of energy simultaneously.

Something we are also very proud of is that on the first floor, we have a public facility run by city hall. We have managed to convince the city to have their Fab Lab Application Laboratory, a place that people can use to transform domestic things like fabricating a small piece of furniture into a table or shelf, whatever they need for their homes. So, it’s very interesting to understand the whole building not only as a destination for consuming resources but also as a carbon sink and a place where you can generate energy and food.

Karl van Es: It sounds very exciting. I have one last question, and it’s a bit on the lighter side. Because we are an architectural and travel blog, we usually ask our guests what their favorite city or building is that changed their perspective on architecture. It’s funny that you’re based in Barcelona, because for me, that building was La Sagrada Familia. I remember my time as a student traveling through Barcelona and stepping into it for the first time, and it completely changed my understanding of what a building could be.

Daniel Ibañez: Totally.

Karl van Es: Is there any building or city that really had that same effect on you?

Daniel Ibañez: Yeah, that’s a funny question. I mean, I have a few cities and buildings that I could point to in general, but even though I have not been able to carve out the time to travel there, I am very much in love with Japan because I think for many years they have developed a construction culture over many centuries that stems from a connection with the forest and a knowledge that’s been developed over time. It’s so sophisticated and so ahead of many of the things that we are trying to do. Now I love many of the Kengo Kuma buildings and others like them that are obviously fantastic. But if you ask me, where do you want to travel and what types of businesses would you like to see? I would say Japan and all the vernacular architecture made there that connects places together. From the typologies to the way they managed their forests, this is a very interesting model that we should be replicating in the future for other places.

I also love very much that I have had a lot of relations over the years with Chile. Chile is a beautiful country in the south of Latin America that is extremely long. It’s almost four thousand kilometers long and has many different climates and tree species. The forestry potential is huge, and it has amazing landscapes. Beautiful architecture is being built there, and a new generation of architects is doing fantastic work, so that’s another place that is very magical, not because of the history that they are inheriting like Japan, but because of the potential I see there of really leading a revolution on mass timber because they have great sources. Fantastic. Kind of like landscapes and an opportunity to build a country that could be very exciting on that model.

Karl van Es: That’s interesting about Japan and Chile. I’ve always been fascinated with Japanese joinery; they don’t really use nails traditionally in their construction, and I’ve always wondered how that could be applied in a contemporary way using CLT and mass timber. Do you see a potential future without nails with the way the industry is going?

Daniel Ibañez: Absolutely. We try to push the limits. One of the prototypes we did three years ago was called the Voxel Quarantine Cabin. It was conceived in the middle of COVID, and we decided to create a smaller space where people could stay by themselves and be completely self-sufficient for 14 days before joining the community as a buffer to prevent COVID spreading to the wider community. With that prototype, we didn’t use any mechanical screws. All the CLT panels were laminated so that they could be connected. We used types of joinery and types of species of trees that you knew could be elongated and cause friction between them to allow the panels to stack into place.

Obviously, this is a basic version of what the Japanese have been doing for many centuries, but it’s miraculous how the joints interlock; nobody could pull them apart. It’s so beautiful and without mechanical intervention. I think one of my dreams, in a way, is to start connecting all the potentials of industrialization and the digital fabrication technologies back to those traditions.

Karl van Es: It sounds fascinating. And maybe after you’ve been able to visit Japan and transfer that learning, we can bring you back on and you can talk about that process. But for now, thank you very much for taking the time to sit down with me. If people are interested in learning more about you and the IAAC, where can we direct them?

Daniel Ibañez: Yes. We are present pretty much everywhere on-line. Through our website, IAAC.net, as well as on Instagram and LinkedIn, to name a few. Any designers or people that are really invested in these important challenges that we have ahead of us, with the idea of not just being apologetic about it but really being creative and forward-thinking and using our work capacities to start designing and building a better world that we will need, please reach out. Absolutely.

Karl van Es: Great. Well, thanks again, and best of luck in your future work, research, and life in Barcelona.

Daniel Ibañez: Thank you so much for your time, Karl.