It was 6 am on a bitter cold Toronto morning just hours after the city’s largest snowfall of the year. Some days before I had arranged an interview with London architect Steven Chilton to discuss his latest work, his process, and what inspires him. Leading up to our Skype call, Steven remained somewhat of a mystery to me. Sometime back in October of last year he graciously shared one of his projects with me, a stunning design for a theatre in Wuxi that is currently under construction. Since then, we’ve exchanged emails and he’s shared some other projects he’s worked on. Wuxi went on to be featured on CNN, and his designs became bigger and bolder.

I decided that I needed to meet Steven and uncover the face which remained largely enigmatic up until now. I wanted to know more about his work and what motivates him. We ended up talking for the better part of an hour about his time at Marks Barfield Architects (the creator’s of the London Eye). We discussed his near-win for the design of the 2020 UK Pavilion in Dubai, and the disappointment that comes with putting your time and energy into one thing only to come up empty-handed in the end. We talked about his use of technology in design and his current project with Epic Games, the innovators behind Fortnite. We ended by talking about his childhood, and how the toys and adolescent shenanigans of his youth inspired the architecture he does now.

The discussion I had with Steven has been edited below for clarity and brevity:

You mentioned that your company, Steven Chilton Architects started out about 3 years ago. Did you have any clients initially or did you decide to just go out on your own and see what you could do?

Pretty much that. Prior to that, I first worked for a practice called Marks Barfield Architects that I joined in 1997. I was straight out of university and my first project was the London Eye which was brilliant in terms of learning and taking a project through a complicated planning process to completion.

Witnessing David (Marks) and Julia (Barfield) persuade people that it wasn’t a fairground ride, but something worth existing out of merit was very inspiring. We were a small practice, so it was a really formative experience for me, most incredibly, it was a self-generated project, they were just an architecture couple, who entered a competition for ideas to celebrate the millennium back in 1994. Nobody won, but they just decided to run with the idea they came up with for a giant observation wheel in the middle of London. They set up a company that attracted British Airways to help finance it and through sheer will, hard work and tenacity, got it built. Having now practiced for a few years, you look back and realize how remarkable they were. They were really cool, the experience of working with them instilled a belief that anything was possible, and you should never take no for an answer.

It’s actually pretty ridiculous to think about it now because it’s gone on to have so much success. I believe it’s the most visited tourist attraction in the entire city of London. To go through that much skepticism throughout the design process, and see the public transformation that went on around you – it must have inspired you to think that if I believe in my own work with the same conviction, it may set me up for success with my own work.

Absolutely. It’s one of those things where you don’t realize how much you’ve learned from it, but actually, you are applying many of the lessons learnt on that project in the way you approach your work today. They deserve more recognition and gratitude than I believe they receive, particularly on the south bank of London for kickstarting the regeneration of that whole area. It’s really down to them and I hope their personal achievement isn’t forgotten.

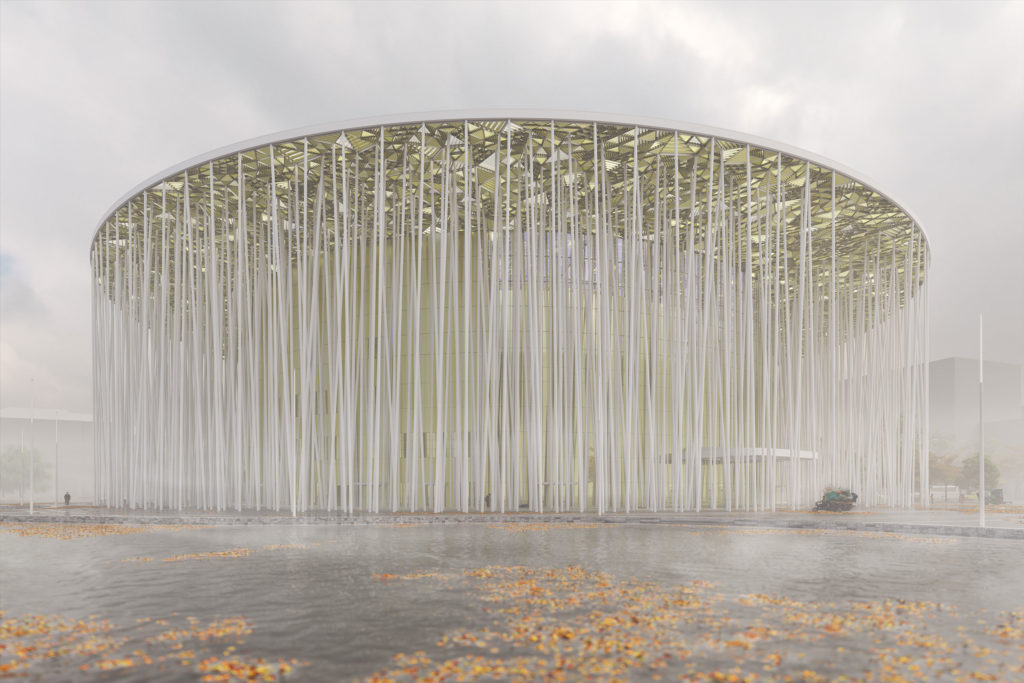

Switching gears to your own recognition, I saw that recently the Wuxi Theatre was featured on CNN as a particular project in 2019 to get excited for. When I first saw the project, I actually thought that it was built already because the images were so good.

That was a big surprise for us. We don’t have a PR company and the recent publicity has more or less happened by accident. We had finished work on a competition to design the UK Pavilion for Expo 2020 towards the end of last summer, something we had worked on full time for nearly 4 months and sadly, we didn’t get it. It was really disappointing, but we thought we would try and get some images of our entry out there and see if we could salvage something from the experience. We sent them to Tom Ravenscroft at Dezeen, along with some of the other projects we had been working on and he picked up on Wuxi. Since then, we have seen that article spread around the internet and found people start to approach you, which is gratifying because we didn’t really know where to start [laughter].

Particularly the work in China, at a certain level, we’ve been slightly reluctant collaborators. We wouldn’t by choice produce work so overtly symbolic,

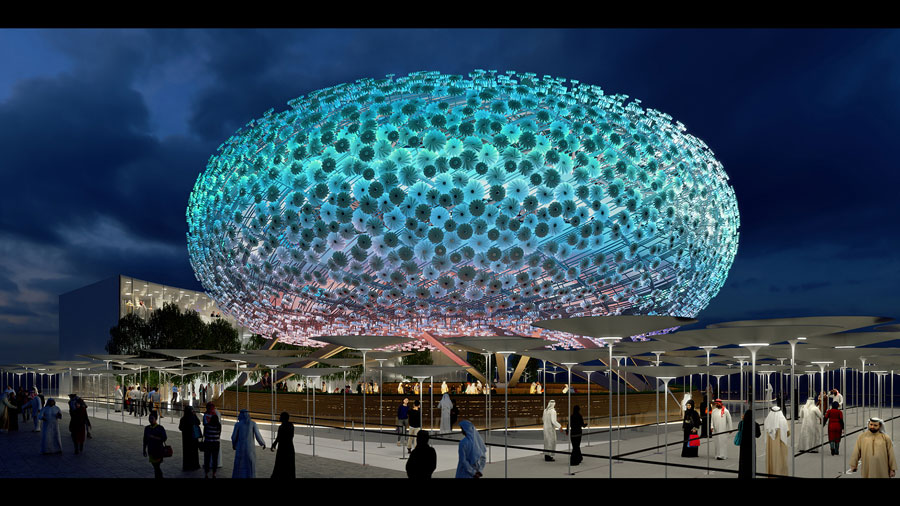

That’s what I find most interesting about your work. It’s quite spectacular but it’s not random. There’s some thinking behind it. I was most blown away by your ‘SATELLITES’ project for Expo 2020 in Dubai, and I thought I could ask you about your design process. You mentioned you have the client’s expectation for design, and you have your own. How did you approach

Well, Expo is probably more representative of our interests, as an exercise in design. It was produced in response to a competition run by the Department of International Trade. The brief contained many of the usual generic points that all expos try to cover such as sustainability, technology and innovation, but the aspect that drew our attention was the requirement to represent the UK’s achievements and capabilities within the satellite industry and AI. We were aware of the importance of figures such as Ada Lovelace and Alan Turing within the realms of computing and AI, however our research into satellites was truly enlightening. We learnt that Isaac Newton was the first person to conceive of the idea of placing objects into orbit around the earth and Arthur C. Clark was the first to propose the idea of geostationary orbit.

Our starting point for Expo was to explore the notion of orbit. Where an idea lends itself, we tend to look for platonic forms as a means of expression, they lend themselves to being more accessible to intuition and able to resonate with memories. For Expo, the obvious starting point was a globe but the height restrictions on the site made it impossible to develop to a sufficiently large volume. Instead, we started looking at a torus which was interesting because its surface can be described by a satellite orbiting the earth over the course of a year. It gave us a starting point to a narrative and

Following the definition of the form, we started to explore ways of expressing satellites and AI? During our research, we came across a team of engineers at Cambridge University who in the ’90s were working on a variety of deployable structures for use in space. We were immediately attracted to a circular folding pattern developed by Professor Simon Guest that he had proposed for use in the development of large, unfurling PV cell arrays for satellites.

Starting with a simple flat disk of a foldable material with sufficient stiffness, he had proposed a folding pattern that did not require the creation of hinges or mechanical joints to open. Instead, a simple twisting motion was all that would be required to fully deploy it in an elegant, and intriguing motion. We learnt that 6000 satellites were predicted to be orbiting the earth during 2020 so this became the number of ‘satellites’ we would populate the surface of the torus with. We developed a simple, motorized mechanism for opening and closing each unit and fitted the inner and outer surface of the folding pattern with an array of

We made it onto the shortlist of 6 teams and presented it to the DIT [ Department of International Trade] who seemed to really like it. However, the organizers and jury were concerned about the environmental impact of the heat and dust on the umbrellas and the ability to deliver them on time. The UK announced their intent to participate quite late so unfortunately the programme didn’t favour our design in their eyes. As you know, Es Devlin won the competition, I think she’s a great ambassador for UK design and the project her team proposed is interesting. So you know, we were sad to lose but I think she’ll do a great job of promoting the UK, and we’re pleased to have been given a platform to demonstrate our capabilities to a wider audience.

Yeah, that’s certainly interesting to hear. Where or what would you say the company is moving towards in the future coming from the platform that EXPO has given you?

Well, most of our experience to date has been in designing theatres and exhibition centres in China. A lot of our projects were carried out for a company called Wanda, they are one of Chinas largest developers. Their cultural tourism projects have recently been acquired by a developer called Sunac and we shall be looking at a new project with them over the next few months.

We’ve actually got a project we’re trying to put together with the guys who make Fortnit.

No way [laughter].

Yes, it’s really interesting. Epic have developed a game development platform called Unreal Engine, it’s really amazing, they’ve invested millions into creating this kit of tools which allow you to develop real-time rendered environments in almost life like detail. Up until recently, it has primarily been used by game developers, but designers from other fields familiar with working in 3d are starting to look at harnessing its potential.

Traditionally, we’ve always used 3Ds Max for our renders. We do most of our

It’s interesting that you discuss the software you use. Technology seems to be something you use heavily in your design process, like your future collaboration like Fortnite. Is technology your go-to design tool or is it just one part of how you design?

We never start our projects thinking, how we can use a specific technology either in the process or the final proposal. Our goal is to create buildings and objects that excite and are beautiful, that captivate and surprise. When we use technology, it is employed creatively in the service of the architecture. There are a lot of practices who work like this, if you look at practices like Fosters and Zaha who were working in the early days of parametric design, you can see how technology has been used and developed to underpin and enable their individual approach’s to design.

We tend to work with engineers who work like that and are excited about pushing the boundaries of what’s possible. I have been fortunate to work with some of the world’s most creative engineers, they share a similar

That’s really interesting. As a way to wrap things up, I’d be interested to hear more about what got you into architecture, what buildings you love, what really drives you to keep going.

I thought about that this morning, I’ve always been really interested in art. It was something which I realized early on I was quite good at, and my father really encouraged it. At school I realized I could do something which people were impressed by, it made me feel good. I did it and carried on doing it from an early age, and that progressed into building things such as balsa wood airplanes and boats. I started building RC cars and making my own vehicles, it was something that I became quite obsessed about and spent a lot of my free time doing. I got into graffiti for a bit actually. I used to wake my little brother up at 2 or 3 am and we’d go out and do pieces on the side of an old garage or in a shelter in the local park [laughter].

I’m horrified now when I think about it, I have 3 children, my eldest daughter, she’s coming up to 12 and I was probably 13 or 14 when we were doing this, what was I thinking? [laughter]. I’d be so shocked now if I found out my kids were doing this, but it was a different time then I suppose.

At school, I knew I wanted to study architecture and it just became my mission. I ended up going to Manchester where my most important experience came during my last year. I chose a unit run by an engineer called Aran Chadwick. His approach to design and materials was very conceptual, which was unusual for Manchester, where up to that point it had been fairly traditional. At the time, he was engineering U2’s PopMart stage and he engaged us in helping him develop hinges for the video screen which was actually more exciting than it sounds.

It was a moment of realisation that there were really interesting and amazing projects being worked on by regular people who just happened to be passionate about design. That experience led me to work at Marks Barfield Architects, and it’s bit fairly interesting ever since.

Steven, thank you so much for sharing your story and work with us. It’s been really fascinating to hear about everything you’ve been up to.

SCA | Steven Chilton Architects is a London based group of highly skilled practitioners connecting cultural insight and the creative use of technology to achieve an unexpected architecture that seeks to embrace, captivate & surprise.