Smritivan Earthquake Memorial & Museum

Architect: Vāstushilpā Sangath

Location: Bhuj, India

Type: Memorial, Museum

Year: 2023

Photographs: Vinay Panjwani, Sohaib Ilyas

Smritivan Earthquake Memorial

The following description is courtesy of the architects. At 8:46 am on January 26, 2001, an earthquake occurred in the Kutch region of Gujarat. Measuring 7.6 on the Richter scale, it irrevocably shook innumerable lives and killed 13,805 people. The destruction of habitat, property and infrastructure ran in billions. The trauma it caused cannot truly be mapped.

Kutch is familiar with the vagaries of nature. It traces its roots at least to the Harappan civilization, thus at least 4500 years. In this period, it has been subject to numerous natural disasters, including cyclones and droughts. Consequently, it has evolved a culture of resilience. Water remains the scarcest natural resource, and so, the region’s ecology, economy, culture, social structure, festivals and struggle for survival all revolve around water.

The precise brief by the then Chief Minister of Gujarat, now Prime Minister, Narender Modi was to “plant a tree for each victim.” A simple yet profound brief. For a tree symbolizes rebirth, renewal and hope, the beginning of the journey of life once again. How better to commemorate the loss of human life than through such a symbolic act of regeneration? The planting of trees also suggested the making of a forest. The forest also symbolizes a collective that is made of many that are diverse.

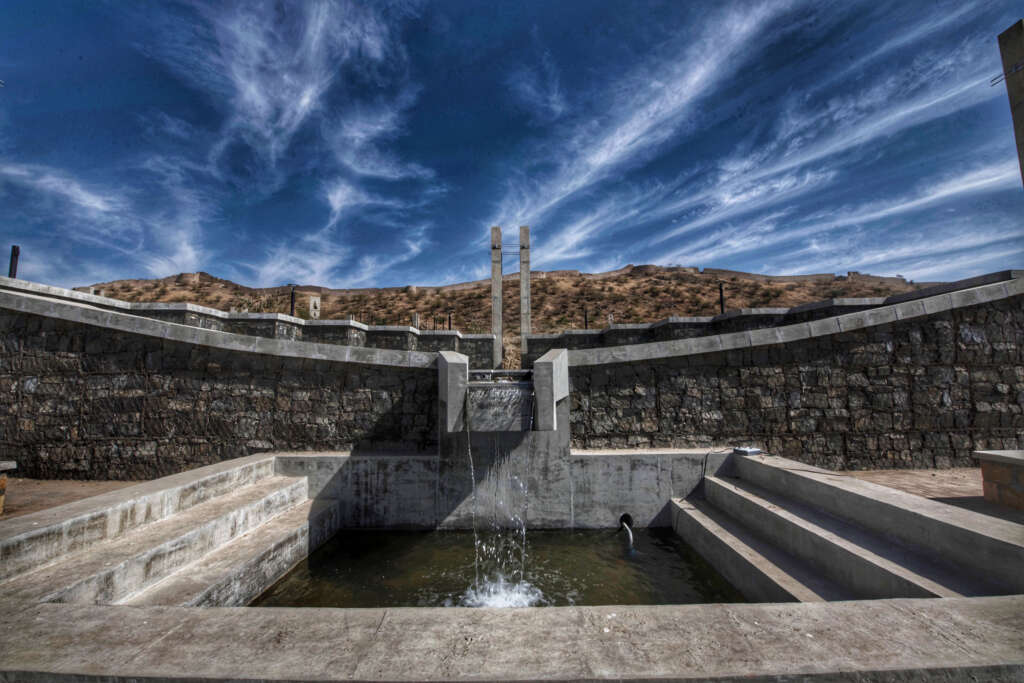

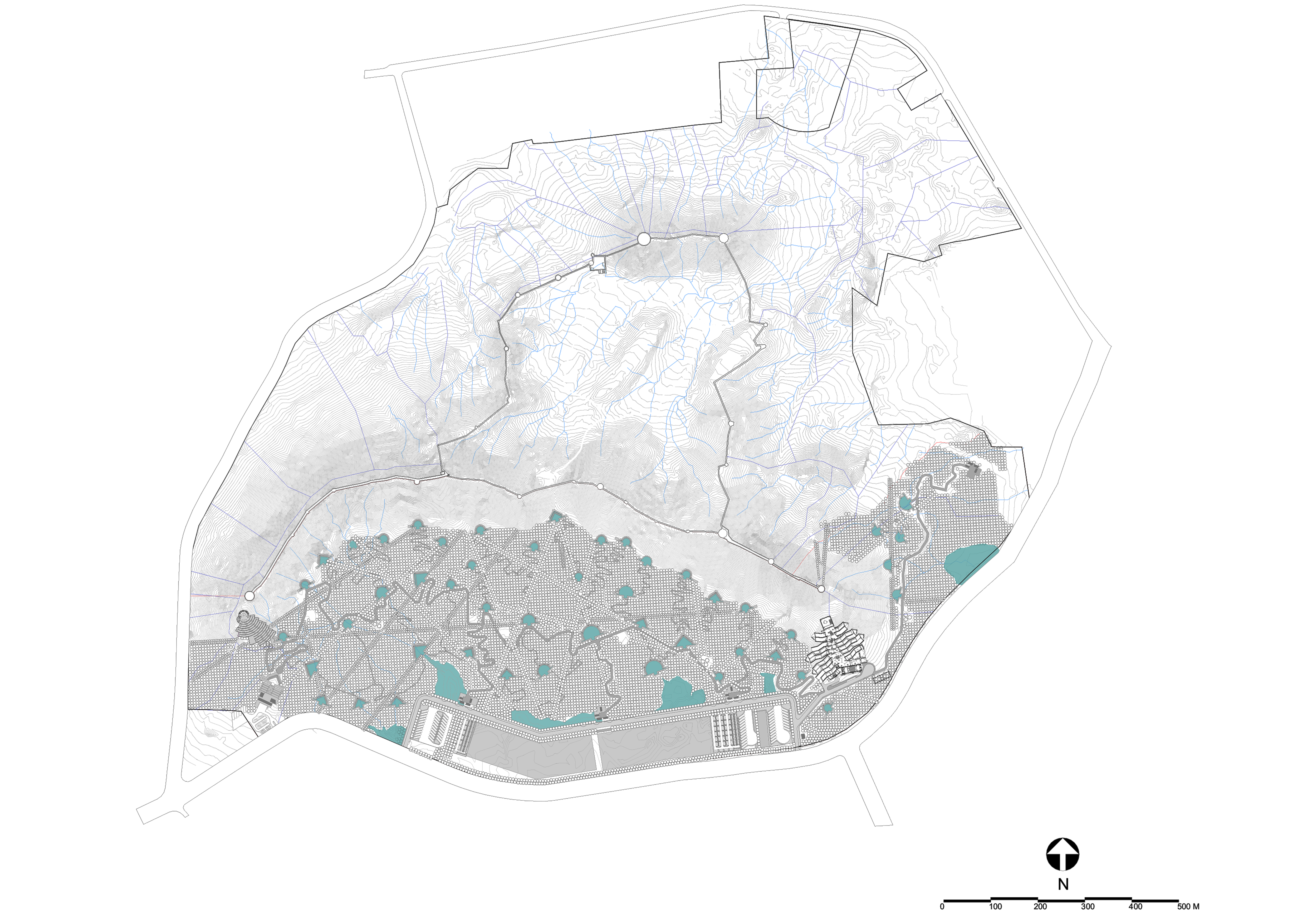

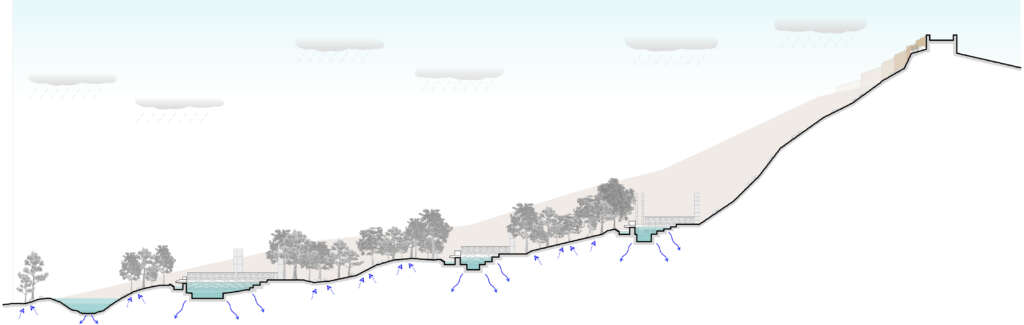

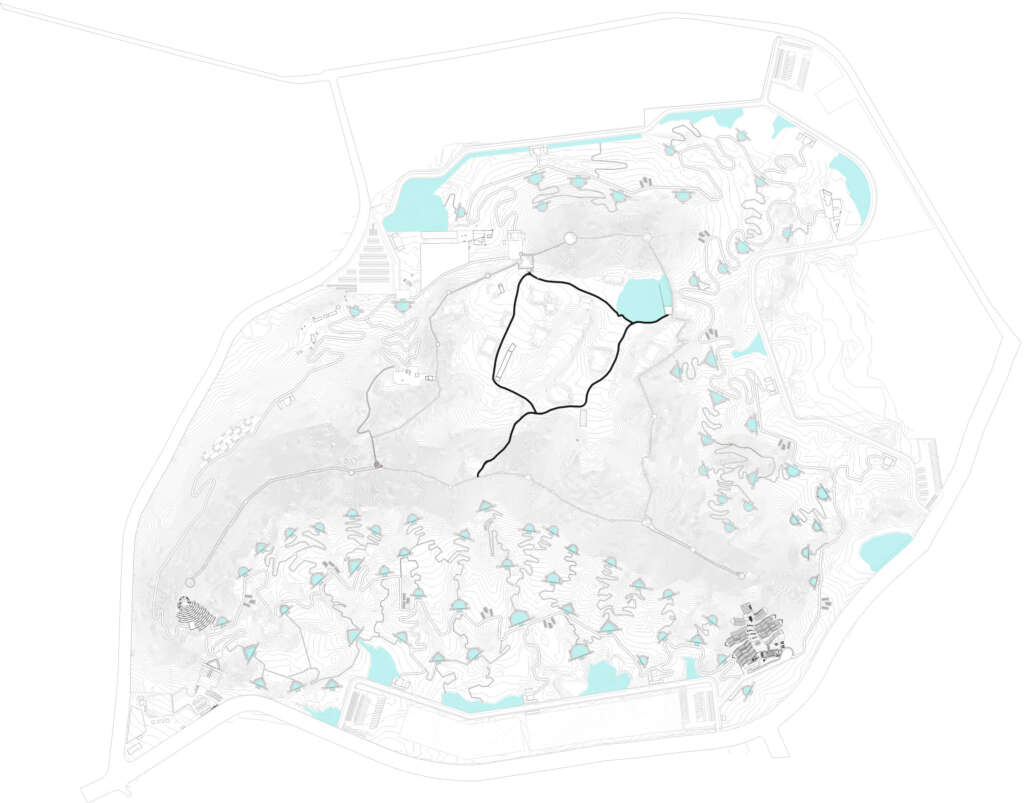

For us, this suggested two intertwined paths. One for the families of the victims who would come as pilgrims to remember their loved ones and the other, a path of sustenance of the trees, of resilience in an arid place such as Kutch. We earnestly believe it is only necessary to initially assist the earth, till the new initiative takes root and then nature takes over. The assistance involved the identification of local species, the paths through which water flows, as well as the soil and nutrients that the water collects on its journey and most importantly thee design of the tanks and places where the water could seep into the earth slowly. The design then evolved by strategically planning small-scale reservoirs on the 452 acres. The first phase of about 199 acres has now been executed.

As nature heals and cultivation grows, the experience of the memorial, of Smritivan changes. Slowly the diverse vegetation will grow into an ecosystem that will merge with the built forms, thus eventually engulfing them into one cohesive maze of green and blue. Smritivan is then neither a monolithic memorial nor a garden, but a living memory, and homage to the hope and resilience of Kutch.

Lastly, Smritivan is meant to be an engaging public space. Thus, along with the reservoirs, a sun point was also created. Located at the top of the hill, it offers vistas of the town that invite reflection. It charts the movement of the sun and moon in the form of a lune-solar calendar, with different cuts in the circular ring marking days of cultural significance. Thus, relating one to the cosmic, reminding one of the larger cosmic event one temporarily inhabits.

Drawings

Smritivan Earthquake Memorial Museum

The museum is located in Bhuj, Gujarat, India on the bhujiyo hill. The museum is a part of the larger smritivan earthquake memorial masterplan, which was made to commemorate the 2001 earthquake of which Bhuj was the epicentre. The museum anchors its journey in the city of Bhuj and the Kutch region’s unique heritage, culture, crafts, and its many villages and wildlife sanctuaries.

The design intent was to create not just a museum but a civic space where the citizens could gather and celebrate their many festivals and more. As with our other projects, we recognise the larger role of such institutions in the making of a city, and ensure that architecture contributes to civic life. The same was true for the Smritivan memorial which also addressed the need for a green lung and park for the city. Programmatically, the various galleries of the museum trace the various crafts and skills of the Kutch region.

The steep slope of the hill meant one had to find a way to sensitively place a building that does not disturb the landscape. The hill is part of the cultural patrimony of the people. Hence building a large-scale box that would contrast with the hill was considered inappropriate. Rather, the contours inform an alternative approach. It dictated a form that recalls the relic of the fort wall which exists on this hill. The built mass is like a line that traces the contours as it zig-zags its way up the hill. It is the natural way that an animal or human uses to climb a hill, or as a pilgrimage route to a holy site. We, as architects, strongly believe that walking is essential to the making of a place, as it enables us to connect to our surroundings in a unique way.

The “soul” of the museum is then this slow climb, a peripatetic journey of a 50m climb punctuated by the various galleries. The spine acts like a veranda where one can pause, reflect and absorb the landscape. This tensile structure also creates a soft glow over the monolithic buildings which are covered in a local stone quarried from near the site. Overall, this central spine of the museum a civic space that operates when the galleries aren’t open.

Temporality remains central to the museum. Thus, each of the galleries’ rooftops is planted with different species of local flora which, as in the hill, changes with the seasons and mark the passage of time. These gardens also host different functions such as temporary exhibits and performances, which enables one to reflect and assimilate, something that is essential to such a museum.

Like most settlements on a landscape, the museum is designed for incremental growth. The modularity of the galleries and the trace of the central spine is such that any extension will always remain aligned to the genius of the place. It is then a settlement, as old as Bhuj, and as young as the memory of the last visit.